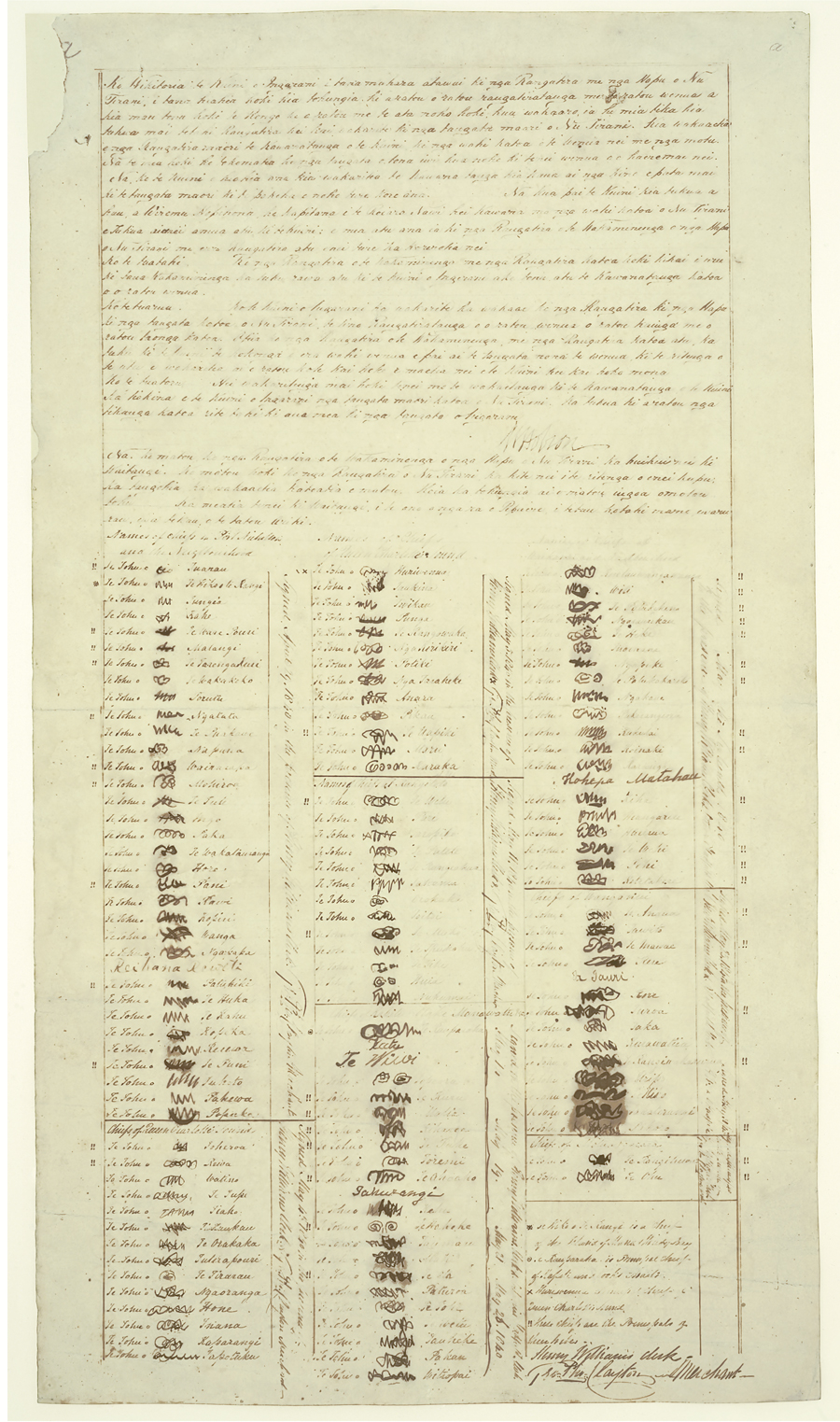

Te Tiriti | The Treaty

Scroll down to read:

Te Tau Ihu O Te Waka a Maui

Waitangi Tribunal Report on Northern South Island Claims

Click here to read the Report Summary

REPORT SUMMARY

On 22 November 2008, the Waitangi Tribunal released its final report on the Treaty claims of iwi and hapu of Te Tau Ihu (northern South Island). The eight recognised iwi are Ngati Apa, Ngati Koata, Ngati Kuia, Ngati Rarua, Ngati Tama, Ngati Toa Rangatira, Te Atiawa, and Rangitane. The report had earlier been released as an incomplete pre-publication edition in order to help with the claimants in their settlement negotiations with the Crown.

The Tribunal inquiry panel comprised Maori land Court Deputy Chief Judge Wilson Isaac (presiding officer), Professor Keith Sorrenson, Pam Ringwood, and John Clarke. The late Rangitihi Tahuparae, a respected kaumatua of Whanganui, passed away on 2 October 2008 between the completion of the report and its publication.

In its report, the Tribunal found that many acts and omissions of the Crown breached the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. In particular, the Tribunal concluded that ownership of all but a tiny fraction of land in the Te Tau Ihu district was lost to Maori without first gaining their free, informed, and meaningful consent to the alienations. Nor did the Crown ensure that fair prices were paid and sufficient lands retained by the iwi for their own requirements.

The Tribunal finds that, contrary to Treaty principles, the Crown granted lands at Nelson and Golden Bay to the New Zealand Company without first ensuring that all customary owners were fairly dealt with. It then proceeded with its own large-scale Wairau and Waipounamu purchases, making predetermined decisions as to ownership which ignored the rights of many Te Tau Ihu Maori or left them with little meaningful choice over the alienation of their lands.

As a result, by as early as 1860 Te Tau Ihu Maori had lost most of their original estate. Thereafter, the Crown failed to actively protect their interests in those lands which remained to them. It also failed to protect their just rights and interests in valued natural resources. Despite petitions from Maori and repeated reports from its own officials, the Crown failed to protect or provide for Maori interests and rights in their customary fisheries and other resources. The result of these failures was grinding poverty, social dislocation, and loss of culture.

The Tribunal found that the totality of Treaty breaches were serious and caused significant social, economic, cultural, and spiritual prejudice to all iwi of Te Tau Ihu. These breaches, the Tribunal considered, required large and culturally appropriate redress.

In an attempt to assist Te Tau Ihu Treaty settlements, the Tribunal made several recommendations for remedies. Having regard in particular to the relatively even spread in terms of social and economic prejudice across all eight Te Tau Ihu iwi, the Tribunal recommended that the total quantum of financial and commercial redress be divided equally between them.

The Tribunal also recommended that site-specific cultural redress should be discussed collectively with all groups involved in Te Tau Ihu Treaty negotiations and that the unique claim of Ngati Apa, whose customary interests within Te Tau Ihu were never extinguished by any kind of deed of cession, needed special recognition. The Tribunal found the Crown’s repeated failure to properly recognise and deal with the Kurahaupo iwi as the legitimate tangata whenua (alongside the northern tribes) of Te Tau Ihu to be a serious breach. It recommended that the Crown take steps to fully recognise and restore the mana of the Kurahaupo iwi.

The Tribunal recommended that the settlement of historical grievances relating to Wakatu Incorporation was most appropriately a matter to be concluded between the Crown and Te Tau Ihu iwi and that matters affecting the shareholders of Wakatu Incorporation since its establishment in 1977 should be resolved between the incorporation and the Crown. It recommended that the Crown enter into parallel negotiations with the Ngati Rarua Atiawa Iwi Trust, with a view to bringing the Whakarewa (Motueka) leases into line with the 1997 Maori reserved lands settlement.

The Tribunal’s report highlighted a number of shortcomings with respect to the current ‘offer-back’ regime under the Public Works Act 1981. It recommended amendments to the Te Ture Whenua Maori Act 1993 and the Public Works Act to address these issues.

The Tribunal also highlighted problems with resource and fishery management regimes and recommended changes and improvements to ensure that these regimes were more consistent with the Treaty. The Crown admitted that the Resource Management Act 1991 was not being implemented in a manner that provided fairly for Maori interests.

Finally, the Tribunal made recommendations with respect to the customary interests of Te Tau Ihu iwi within the statutorily defined Ngai Tahu takiwa. Te Tau Ihu iwi lost the ability to recover their interests in lands within the takiwa, which have been vested in Ngai Tahu as a result of earlier Crown settlement. The Tribunal strongly recommended that the Crown take urgent action to ensure that these breaches did not continue. It also recommended that the Crown negotiate with those Te Tau Ihu iwi identified in the report as having customary interests within the statutorily defined Ngai Tahu takiwa to agree on equitable compensation.

Ngāti Koata Evidence

Reports and Evidence

Click here to see the list of whānau who made submissions to the Waitangi Tribunal

Ariana Eileen Rene

Ben Hippolite

Carl Elkington

Heather Bassett

James Elkington

Dr John Barrington

Josephine Paul

Madsen Elkington

Marlin Elkington

Melanie McGregor

Meto Hopa

Nohorua Kotua

Nolamay Murray-Campbell

Pirihira Paul

Puhanga Tupaea

Rahui Katene

Rawenata Loverna Geiger

Terewai Grace

If you would like a copy of a submission or need any further information please contact pa@ngatikoata.com

Ngāti Koata Deed of Settlement

Deed and Bill

Click here to read the Settlements Summary

The Ngāti Koata Deed of Settlement is the full and final settlement of all historical Treaty of Waitangi claims of Ngāti Koata resulting from acts or omissions by the Crown prior to 21 September 1992, and is made up of a package that includes:

• an agreed historical account and Crown Acknowledgements which form the basis for a Crown Apology to Ngāti Koata

• cultural redress

• financial and commercial redress.

The benefits of the settlement will be available to all members of Ngāti Koata wherever they may live.

The Ngāti Koata settlement was negotiated alongside settlements with the other seven iwi with historical claims in Te Tau Ihu. The settlement legislation to enact the Ngāti Koata Deed of Settlement is drafted as part of an omnibus bill that will implement all Te Tau Ihu Treaty settlements.

Some redress in the Ngāti Koata settlement is joint redress with other iwi or overlaps with redress in other Te Tau Ihu settlements.

General Background

Ngāti Koata has customary interests in northern South Island, a region often referred to as Te Tau Ihu.

In October 2006, the Crown recognised the mandate of Ngāti Koata along with other ‘Tainui Taranaki’ iwi to enter negotiations for a comprehensive Treaty of Waitangi Settlement. The Crown signed terms of negotiations with the mandated negotiator on 27 November 2007.

On 11 February 2009, the Crown and ‘Tainui Taranaki’ iwi, including Ngāti Koata, signed a Letter of Agreement which formed the basis for this settlement.

The Deed of Settlement was initialled on 7 October 2011 and signed on 21 December 2012. The settlement will be implemented following the passage of settlement legislation.

The Office of Treaty Settlements, with the support of the Department of Conservation, Land Information New Zealand, and other government agencies, represented the Crown in day-to-day negotiations.

The Minister for Treaty of Waitangi Negotiations, Hon Christopher Finlayson, represented the Crown in high-level negotiations with Ngāti Koata.

Summary of the Historical Background to the claims by Ngāti Koata

Ngāti Koata first came to Te Tau Ihu (the northern South Island) in the mid-1820s, after receiving a tuku of land from Tutepourangi, and also as part of an invasion. Ngāti Kōata primarily settled at Rangitoto Island, Croisilles, Whakapuaka, and Whakatu.

In 1839 the New Zealand Company signed deeds with other iwi that purported to purchase the entire northern South Island. The following year several Ngāti Koata chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi at Rangitoto Island.

In 1842 the Company presented gifts to local Māori upon establishing its Nelson settlement. In 1844 a Crown-appointed commissioner investigated the Company’s purchases.

He heard only one Māori witness in Nelson before suspending the inquiry to enable the Company to negotiate a settlement. Māori signed deeds of release in return for accepting payments described by the commissioner as gifts to assist settlement rather than payments for the land.

In 1845, on the commissioner’s recommendation, the Crown prepared a Company grant of 151,000 acres in Tasman and Golden Bays which would have reserved 15,100 acres for Māori.

However, the Company objected to several aspects of this grant. In 1848 the Company accepted a new Crown grant for a larger area of land that reserved only 5,053 acres at Nelson and Motueka, and areas in the Wairau and Golden Bay.

Ngāti Koata had negligible involvement in the administration of the Nelson and Motueka reserves, known as ‘Tenths’, which were leased to settlers to generate income that was spent on Māori purposes. From 1887 the Tenths were let under perpetually renewable leases. Rentals were infrequently reviewed and over time inflation reduced rental returns. During the twentieth century the Tenths were reduced by the compulsory acquisition of uneconomic shares and the sale of reserves.

In 1852 the Crown purchased the mineral-rich Pakawau block and paid only for its agricultural value. In 1853 the Crown signed the Waipounamu deed with other iwi, and purported to have purchased most of the remaining Māori land in Te Tau Ihu. Ngāti Koata did not sign the deed but were to receive a share of the purchase money. The Crown used the 1853 deed as the basis for negotiations with resident Ngāti Koata in 1856, which led to the alienation of most of their remaining interests for L100. Rangitoto Island was excluded from this purchase.

The reserves created for Ngāti Koata from the Waipounamu sale were mostly inadequate for customary use or effective development. In 1883 and 1892 the Native Land Court awarded ownership of the reserves and Rangitoto Island to individual Ngāti Koata. Over time, sales and successions to the titles made the lands increasingly fragmented and uneconomic.

In 1883 Ngati Koata participated in the Native Land Court’s title investigation of Whakapuaka.

Ngati Koata claimed interests on the basis of the tuku and ongoing occupation. The Court deemed that Ngati Koata did not have interests and they were excluded from ownership. Ngati Koata were again excluded at a rehearing of the block in 1937.

By the late nineteenth century, some Ngāti Koata were virtually landless. In 1894 the Crown allocated some landless Ngāti Koata individuals land at Te Māpou and Te Raetihi, but did not issue titles to them until 1968.

Ngāti Koata struggled to secure safe drinking water and social services on their reserves and Rangitoto Island well into the twentieth century. Many Ngāti Koata came to Nelson for work, educational and health purposes. A Māori hostel in Nelson used by Ngāti Koata families was frequently overcrowded resulting in unhygienic conditions.

By the end of the twentieth century most of Ngāti Koata’s remaining land, including their reserves and Rangitoto Island, had been sold. Virtual landlessness has meant that Ngāti Koata has lost connection and access to many of their traditional resources and sites, and the demise of a strong cultural base.

Crown Acknowledgements and Apology

The Deed of Settlement contains a series of acknowledgements by the Crown where its actions arising from interactions with Ngāti Koata have breached the Treaty of Waitangi and its principles.

The Crown apologises to Ngāti Koata for its acts and omissions which have breached the Crown’s obligations under the Treaty of Waitangi. These include: the Crown’s failure to adequately protect the interests of Ngāti Koata during the process by which land was granted to the New Zealand Company; the failure to provide sufficient reserves, including ‘tenths’ reserves; the administration of the tenths reserves; the failure to adequately protect Ngāti Koata interests during Crown purchases between 1853 and 1856; the operation and impact of the native land laws on Ngāti Koata land; the failure to effectively implement the landless natives reserves scheme; and the failure to ensure Ngāti Koata retained sufficient land for their future needs.

Cultural redress

1. This redress recognises the traditional, historical, cultural and spiritual association of Ngāti Koata with places and sites owned by the Crown within their rohe. This allows Ngāti Koata and the Crown to protect and enhance the conservation values associated with these sites.

1(A) Vesting of sites

The settlement provides for six sites to be vested in Ngāti Koata and one site jointly vested in Ngāti Koata and more than one other iwi with Te Tau Ihu claims totalling approximately 28.52 hectares. The vesting of these sites is subject to specific conditions including protection of conservation values and public access. This redress will be known as Ngā Maramara Hirahira.

Sites to be vested in Ngāti Koata are:

• Catherine Cove, approximately 1.0 hectare

• Whangarae Bay (Okiwi Bay), approximately 0.09 hectares

• Lucky Bay, approximately 15 hectares

• Wharf Road (Okiwi Bay), approximately 1.4 hectares

• Whangarae Estuary, approximately 10 hectares

• Moukirikiri Island, approximately 0.826 hectares.

Sites to be jointly vested in Ngāti Koata and more than one other iwi with Te Tau Ihu claims:

• Mātangi āwhio (Nelson), approximately 0.2061 hectares.

French Pass School and Teachers Residence (approximately 0.2009 hectares) will vest in Ngāti Koata if it is cleared under the Public Works Act 1981.

1(b) Overlay Classification

An overlay classification (known as He Uhi Takai in the Ngāti Koata settlement) acknowledges the traditional, cultural, spiritual and historical association of Ngāti Koata with certain sites of significance.

The declaration of an area as an overlay classification provides for the Crown to acknowledge iwi values in relation to that area.

The settlement provides for overlay classifications over:

• Takapourewa/Takapourewa Nature Reserve

• Whakaterepapanui/Wakaterepapanui Island Recreation Reserve

• Rangitoto ki te Tonga/D’Urville Island site

• French Pass Scenic Reserve.

1(c) Statutory Acknowledgements and Deeds of Recognition

Statutory Acknowledgements (known as Ngā Tapuwae o Ngā Tupuna, in the Ngāti Koata settlement) register the special association Ngāti Koata has with an area, and will be included in the settlement legislation. Statutory Acknowledgements are recognised under the Resource Management Act 1991 and Historic Places Act 1993. The acknowledgements require that consent authorities provide Ngāti Koata with summaries of all resource consent applications named in the acknowledgements.

Deeds of Recognition (known as Te Waka Hourua in the Ngāti Koata settlement) oblige the Crown to consult with Ngāti Koata and have regard to their views regarding the special association Ngāti Koata has with a site. They also specify the nature of the input of Ngāti Koata into management of those areas by the Department of Conservation.

The Crown offers a Statutory Acknowledgement and Deed of Recognition over the following areas:

• Maungatapu

• Matapehe

• Moawhitu (Rangitoto ki te Tonga/D’Urville Island)

• Askews Hill quarry site in Taipare Conservation Area

• Cullen Point

• Penguin Bay (Rangitoto ki te Tonga/D’Urville Island)

• Otuhaereroa Island

• Motuanauru Island

• Maitai River and its tributaries;

• Waimea River, Wairoa River and Wai-iti River and their tributaries

• Te Hoiere/Pelorus River and its tributaries

• Whangamoa River and its tributaries.

The Crown offers a Coastal Statutory Acknowledgement over the following area:

• Te Tau Ihu coastal marine area.

Statutory Acknowledgements and Deeds of Recognition are nonexclusive redress, meaning more than one iwi can have a Statutory Acknowledgement or Deed of Recognition over the same site.

1(d) Conservation Statutory Adviser

The Deed of Settlement provides for the appointment of a Te Pātaka a Ngāti Koata trustee as a conservation statutory adviser (known as Ka Tika Te Reo Ka Puawai in the Ngāti Koata settlement). The Statutory Adviser is to provide advice to the Minister of Conservation in relation to the management and restoration of native flora and fauna in the following areas:

• Takapourewa

• Whangarae

• Moawhitu.

1(e) Ruruku Ngā Tai

The Deed of Settlement provides for Ruruku Ngā Tai, a statement of the maritime association of Ngāti Koata. It includes an Iwi Management Plan that has been lodged with Tasman District Council, Nelson City Council and Marlborough District Council.

1(f) Takapourewa Operational Plan

The settlement provides for the Te Pātaka a Ngāti Koata trustees and the Director-General of Conservation to jointly prepare and approve an operational plan for Takapourewa (known as He Whiringa Whakaaro in the Deed of Settlement). The operational plan will include the process for the customary use of fauna and flora by Ngāti Koata.

1(g) Statement of Historical Association

The settlement will provide the Crown’s acknowledgement of the statement by Ngāti Koata of their historical association with West of Separation Point/Te Matau. This will be known as Tangi Wairua te Matangi in the Ngāti Koata settlement.

1(h) Geographic Names

The Te Tau Ihu settlements will provide for 53 geographic names to change and 12 sites which do not currently have official names to be assigned geographic names. The full list of place name changes is included in the Ngāti Koata Deed of Settlement, available at ots.govt.nz

1(i) Minerals Fossicking

The settlement provides for the river beds within a specified area to be searched for natural material with the permission of the trustees of Te Pātaka a Ngāti Koata.

1(J) Right of way for Moawhitu fishing reserve

The settlement will require the Minister of Conservation to provide Ngāti Koata an unregistered right of way easement in gross in Moawhitu. This redress will be known as He Putanga Hua in the Ngāti Koata settlement.

Relationships

2(a) Relationshi p redress

The Deed of Settlement provides for the promotion of relationships between Ngāti Koata and local authorities. Nelson City Council, Tasman District Council, Marlborough District Council and Buller District Council are encouraged to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding with Ngāti Koata.

2(b) Protocols

Protocols (known as Ngā Maunga Kōrerō in the Ngāti Koata settlement) will be issued to encourage good working relationships on matters of cultural importance to Ngāti Koata. Conservation, fisheries, taonga tuturu and minerals protocols will be issued.

2(c) Letters of introduction

The Deed of Settlement provides for the promotion of relationships between Ngāti Kōata and museums. This redress will be known as Ngā Wāwāhio and provides a link to the Tainui roots of Ngāti Kōata. The Crown will write letters of introduction to Te Papa Tongarewa, Canterbury Museum, Otago Museum and Nelson Provincial Museum.

2(d) River and Freshwater Advisory Committee

The Deed of Settlement provides for Ngāti Kōata to participate in an advisory committee providing input into local authority planning and decision making in relation to the management of rivers and fresh water under the Resource Management Act 1991, within the jurisdictions of Marlborough District Council, Nelson City Council and Tasman District Council.

2(e) Memorandum of Understanding

The settlement provides for a Memorandum of Understanding (known as Te Kupu Whakairo in the Deed of Settlement) to be created between Ngāti Koata and the Department of Conservation. The Memorandum of Understanding will require that when the Department of Conservation undertake certain activities within Whangarae Bay, the trustees of Te Pātaka a Ngāti Koata will be consulted.

Financial and commercial redress

3. This redress recognises the losses suffered by Ngāti Koata arising from breaches by the Crown of its Treaty of Waitangi obligations. It will provide Ngāti Koata with resources to assist them in developing their economic and social well-being.

3(a) Financial Redress

Ngāti Koata will receive a financial settlement of $11,760,000 in recognition of all their historical claims. Interest that has been accumulating since the Agreement in Principle was signed in February 2009 will also be paid.

3(b) Commercial Redress

Ngāti Koata will purchase four properties at settlement date that will be leased back to the Crown. Ngāti Koata has a further 16 deferred selection properties that are available for purchase by Ngāti Koata for three years after settlement date.

Ngāti Koata will have the ability to purchase more than 9,000 hectares of the licensed Crown forest land in Te Tau Ihu, through which Ngāti Koata will receive a further (approximately) $7.75 million in accumulated rentals, currently held by the Crown Forestry Rental Trust.

Ngāti Koata will have a right of first refusal over a number of listed properties for a period of 169 years. They will also have a right of first refusal over Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology for 169 years.

Ngāti Koata will also have shared rights of first refusal with other iwi in Te Tau Ihu over other types of Crown properties in Te Tau Ihu for 100 years from the settlement date.

Questions and Answers

1. What is the total cost to the Crown?

The total cost to the Crown of the settlement redress outlined in the Deed of Settlement is $11.76 million (plus interest accrued since the signing of the Agreement in Principle), and the value of the cultural redress properties to be vested and transferred for no consideration.

2. Is there any private land involved?

No. In accordance with Crown policy, no private land is involved.

3. Are the public’s rights affected?

No, all existing public rights to the area affected by this settlement will be preserved.

4. Are any place names changed?

Yes. The Deed of Settlement, along with other Te Tau Ihu Deeds of Settlement, will provide for 12 new place names and 53 name changes.

5. What happens to memorials on private titles?

The legislative restrictions (memorials) placed on the title of Crown properties and some former Crown properties now in private ownership, will be removed once all Treaty claims in the area have been settled.

6. When will the settlement take effect?

The settlement will take effect following enactment of the settlement legislation.

7. Does Ngāti Koata have the right to come back and make further claims about the behaviour of the Crown in the 19th and 20th centuries?

No. If a Deed of Settlement is ratified and passed into law, both parties agree it will be a final and comprehensive settlement of all the historical (relating to events before 21 September 1992) Treaty of Waitangi claims of Ngāti Koata. The settlement legislation, once passed, will prevent Ngāti Koata from re-litigating their claim before the Waitangi Tribunal or the courts.

The settlement package will still allow Ngāti Koata or members of Ngāti Koata to pursue claims against the Crown for acts and omissions after 21 September 1992, including claims based on the continued existence of aboriginal title or customary rights.

The Crown also retains the right to dispute such claims or the existence of such title rights.

8. Who benefits from the settlement?

All members of Ngāti Koata wherever they may now live.

WAI 262

The Flora & Fauna Claim

The Flora and Fauna Wai 262 Claim was lodged on 9 October 1991 by six claimants on behalf of themselves and their iwi:

- Haana Murray (Ngāti Kurī),

- Hema Nui a Tawhaki Witana (Te Rarawa),

- Te Witi McMath (Ngāti Wai),

- Tama Poata (Ngāti Porou),

- Kataraina Rimene (Ngāti Kahungunu), and

- John Hippolite (Ngāti Koata)

The claim is about the place of Māori culture, identity and traditional knowledge in New Zealand’s laws, and in government policies and practices. It concerns who controls Māori traditional knowledge, who controls artistic and cultural works such as haka and waiata, and who controls the environment that created Māori culture. It also concerns the place in contemporary New Zealand life of core Māori cultural values such as the obligation of iwi and hapū to act as kaitiaki towards taonga such as traditional knowledge, artistic and cultural works, important places, and flora and fauna that are significant to iwi or hapū identity.

Following the Hearings the Waitangi Tribunal released the Ko Aotearoa Tēnei report. Links to this report and other important documents can be found on the links to the right.

Wai 262 Statement of Claim

Ko Aotearoa Tēnei: A Report into Claims Concerning New Zealand Law and Policy Affecting Māori Culture and Identity. Te Taumata Tuarua volume 2

Report Summary

On 2 July 2011, the Waitangi Tribunal released its report on the Wai 262 claim relating to New Zealand’s law and policy affecting Māori culture and identity.

Ko Aotearoa Tēnei (‘This is Aotearoa’ or ‘This is New Zealand’) is the Tribunal’s first whole-of-government report, addressing the work of around 20 government departments and agencies and Crown entities.

It is also the first Tribunal report to consider what the Treaty relationship might become after historical grievances are settled, and how that relationship might be shaped by changes in New Zealand’s demographic makeup over the coming decades.

The report concerns one of the most complex and far-reaching claims ever to come before the Waitangi Tribunal. The Wai 262 claim is commonly known as the indigenous flora and fauna and cultural and intellectual property claim. As the report’s preface puts it:

the Wai 262 claim is really a claim about mātauranga Māori – that is, the unique Māori way of viewing the world, encompassing both traditional knowledge and culture. The claimants, in other words, are seeking to preserve their culture and identity, and the relationships that culture and identity derive from.

The report is divided into two levels, each of which is designed to be read independently: a shorter summary layer subtitled Te Taumata Tuatahi, which aims to be accessible to a general readership, and a fuller, two-volume layer subtitled Te Taumata Tuarua. Both layers have an introduction, eight thematic chapters and a conclusion.

The first volume of Te Taumata Tuarua introduces the report and contains its first four chapters. Chapter 1 considers the Māori interest in the works created by weavers, carvers, writers, musicians, artists, and others in the context of New Zealand’s intellectual property law, particularly copyright and trade marks.

Chapter 2 examines the genetic and biological resources of the flora and fauna with which Māori have developed intimate and long-standing relationships, and which are now of intense interest to scientists and researchers involved in bioprospecting, genetic modification, and intellectual property law, particularly patents and plant variety rights.

The next two chapters consider Māori interests in the environment more broadly, first in terms of the wide-ranging aspects of the environment controlled by the Resource Management Act (chapter 3), and then with regard to the conservation estate managed by the Department of Conservation (chapter 4).

The second volume of Te Taumata Tuarua contains the final four chapters of the report. Chapter 5 focuses on the Crown’s protection of te reo Māori (the Māori language) and its dialects, and considers in depth the current health of the language. A prepublication version of this chapter was released in October 2010.

Chapter 6 considers those agencies where the Crown owns, funds, or oversees mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge and ways of knowing) and is thus effectively in the seat of kaitiaki (cultural guardian). These agencies operate in the areas of protected objects, museums, arts funding, broadcasting, archives, libraries, education, and science.

Chapter 7 then examines the Crown’s support for rongoā Māori or traditional Māori healing. It also traverses the principal historical issue covered in the report, the passage and impact of the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907.

Chapter 8 addresses the Crown’s policies on including Māori in the development of New Zealand’s position concerning international instruments such as the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Each chapter ends with a brief summary of the Tribunal’s recommendations for reform, and a concluding chapter brings together its overall conclusions and recommendations.

An appendix provides a brief procedural history of the inquiry, outlining the origins and development of the claim, the claimants, the scope of the claim issues and the two rounds of hearings.

Ko Aotearoa Tēnei Report Summary

Ko Aotearoa Tēnei: A Report into Claims Concerning New Zealand Law and Policy Affecting Māori Culture and Identity. Te Taumata Tuarua volume 2

Report Summary

On 2 July 2011, the Waitangi Tribunal released its report on the Wai 262 claim relating to New Zealand’s law and policy affecting Māori culture and identity.

Ko Aotearoa Tēnei (‘This is Aotearoa’ or ‘This is New Zealand’) is the Tribunal’s first whole-of-government report, addressing the work of around 20 government departments and agencies and Crown entities.

It is also the first Tribunal report to consider what the Treaty relationship might become after historical grievances are settled, and how that relationship might be shaped by changes in New Zealand’s demographic makeup over the coming decades.

The report concerns one of the most complex and far-reaching claims ever to come before the Waitangi Tribunal. The Wai 262 claim is commonly known as the indigenous flora and fauna and cultural and intellectual property claim. As the report’s preface puts it:

the Wai 262 claim is really a claim about mātauranga Māori – that is, the unique Māori way of viewing the world, encompassing both traditional knowledge and culture. The claimants, in other words, are seeking to preserve their culture and identity, and the relationships that culture and identity derive from.

The report is divided into two levels, each of which is designed to be read independently: a shorter summary layer subtitled Te Taumata Tuatahi, which aims to be accessible to a general readership, and a fuller, two-volume layer subtitled Te Taumata Tuarua. Both layers have an introduction, eight thematic chapters and a conclusion.

The first volume of Te Taumata Tuarua introduces the report and contains its first four chapters. Chapter 1 considers the Māori interest in the works created by weavers, carvers, writers, musicians, artists, and others in the context of New Zealand’s intellectual property law, particularly copyright and trade marks.

Chapter 2 examines the genetic and biological resources of the flora and fauna with which Māori have developed intimate and long-standing relationships, and which are now of intense interest to scientists and researchers involved in bioprospecting, genetic modification, and intellectual property law, particularly patents and plant variety rights.

The next two chapters consider Māori interests in the environment more broadly, first in terms of the wide-ranging aspects of the environment controlled by the Resource Management Act (chapter 3), and then with regard to the conservation estate managed by the Department of Conservation (chapter 4).

The second volume of Te Taumata Tuarua contains the final four chapters of the report. Chapter 5 focuses on the Crown’s protection of te reo Māori (the Māori language) and its dialects, and considers in depth the current health of the language. A prepublication version of this chapter was released in October 2010.

Chapter 6 considers those agencies where the Crown owns, funds, or oversees mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge and ways of knowing) and is thus effectively in the seat of kaitiaki (cultural guardian). These agencies operate in the areas of protected objects, museums, arts funding, broadcasting, archives, libraries, education, and science.

Chapter 7 then examines the Crown’s support for rongoā Māori or traditional Māori healing. It also traverses the principal historical issue covered in the report, the passage and impact of the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907.

Chapter 8 addresses the Crown’s policies on including Māori in the development of New Zealand’s position concerning international instruments such as the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Each chapter ends with a brief summary of the Tribunal’s recommendations for reform, and a concluding chapter brings together its overall conclusions and recommendations.

An appendix provides a brief procedural history of the inquiry, outlining the origins and development of the claim, the claimants, the scope of the claim issues and the two rounds of hearings.

History of the Wai 262 Claim

Prepared by Oliver Sutherland and the late Murray Parsons in conjunction with Moana Jackson and the whanau of claimants, June 2011